Logging the Virgin Forests of West Virginia

If you’ve ever backpacked in the West Virginia mountains, there’s one fact that becomes quickly evident. Virtually every hollow, every stream, and every mountain has a railroad grade. In some places, the railroad ties are still on the ground. In others, visitors might run across a rusting washtub in the middle of the woods, or even an occasional railroad spike or rail. Regardless of how far back you go or how deep into the wilderness, the grades are there – mute testament to the energy of man, power of the dollar, and the complete destruction of the West Virginia forest ecosystem.

In many years of travel through the West Virginia backcountry, I’ve often wondered what the original forest must have looked like. Could I possibly envision walking through miles and miles of spruce forest with trees growing to a size difficult to comprehend? What would it have been like to camp in these hollows and flats filled with massive trees and extensive laurel and rhododendron thickets, where in places the cover was so thick that sunlight never reached the ground? What would I have felt standing next to a poplar soaring 140 feet into the sky? I can only imagine.

The destruction of these once magnificent forests in the 1880’s and stretching over a forty year period was “complete”. Virtually every tree on every mountain was cut down and hauled out by horse, steam rigger, or train. The logging companies that swarmed over the West Virginia mountains removed these trees “with pride”. This was the age of the Industrial Revolution – man’s superiority over nature. The days of the railroad, cattle and timber barons, and industrial giants like J.P. Morgan. Progress was good. Nature existed to serve man’s superior intellect and needs.

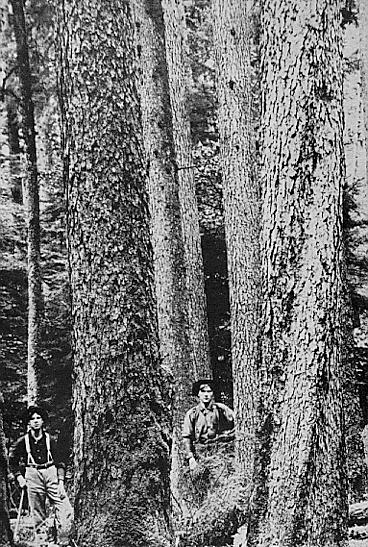

As is true of all the “major undertakings” of man, clearcutting and the ultimate devastation of the Allegheny forest ecosystem was documented in pictures by the various logging companies that cleared the land. Today, for those that have visited the backcountry regions where few men originally roamed, these pictures bring to life a time in our history when a tree was more valuable as a clothspin than a national resource for recreation and ecosystem preservation. The photos show what once was, and what is now lost to history under the lumberman’s saw.

The Allegheny Forest – Before Man

Very little descriptive data is available on the original forests. It remained for George Washington while exploring the valley of the Great Kanawa to leave one of the first meager description of trees in this wild uncharted land. On November 4, 1770, while traveling along the Kanawa River he wrote in his journal, “Just as we came to the hills, we met with a Sycamore…..of a most extraordinary size, it measuring three feet from the ground, forty-five feet round, lacking two inches; and not fifty yards from it was another, thirty-one feet round.” As late as 1870, we read that “at least 10,000,000 acres (of the 16,640,000 acres of land in West Virginia) are still in all the vigor and freshness of original growth”.

Washington’s description whets the imagination. What did this huge, virgin forest originally look like?? A description of some of the trees that were cut in the forest may help shed light on this question:

The most valuable logging tree in the State was red spruce. It occurred over vast areas on the tops of mountains and on the plateaus. Prior to the logging effort, there was 469,000 acres of spruce in the Allegheny forest. The typical red spruce was 60 to 90 feet with a diameter of 2 to 4 feet. The greatest stand of red spruce in the world (in terms of size and quality) could be found along the upper Red Creek drainage in what is now Dolly Sods Wilderness. The entire region was clearcut.

On the northern exposures and in cool, wet ravines, hemlock could be found. The largest known hemlock tree cut during the logging effort was seven feet in diameter at the base and was located at Curtin, Nicholas County, WV. The best growth of hemlock occurred along Cranberry, Williams, and Gauley rivers, where the trees grew to 6 to 7 feet in diameter. (This area included part of the Cranberry Wilderness, where few hemlocks now remain.) The entire area was clearcut.

White oak, the largest timber tree in the original forest, often attained a height of 100 feet and a diameter of over 6 feet. It could be found on the slopes and ridges of dry, thin soils derived from sandstone and shale. The largest known tree ever cut in West Virginia was a White Oak, and it is pictured here. The other oaks, along with this world record tree, were all clearcut.

The most important cove hardwood tree was the Yellow Poplar, a species that grew to enormous size. The typical poplar attained a height of 120 to 140 feet, and a diameter of 7 to 9 feet, with a distance to the first limb of 80 feet. Several poplars 10 and 11 feet in diameter were located by loggers and cut down. Large poplars were not isolated freaks in the original forest. They often occurred in nearly pure stands. They were all clearcut.

On the ground could be found extensive undergrowth. The following is an excerpt from an account written in 1857 by David Strother concerning the Canaan Valley/Dolly Sods region:

These extensive laurel brakes, along with virtually every other standing tree in the Alleghenies, were clearcut.